Claude Cowork: The AI Agent That Built Itself in 10 Days

On January 12, 2026, Anthropic launched Claude Cowork, an AI productivity tool that represents a fundamental shift in how artificial intelligence interacts with work. What makes this launch particularly significant isn't just the product itself. It's how it was created. Claude Cowork was built in approximately 10 days using Claude Code, the AI coding assistant, to write "pretty much all" of the code.

Executive Summary: A Milestone for Recursive AI Development

Claude Cowork extends the capabilities of Claude Code (Anthropic's developer-focused agentic coding tool) to non-technical users. It transforms AI from a conversational assistant into an autonomous agent capable of executing complex, multi-step tasks with direct access to local files.

The product marks a transition from chat-based AI to outcome-based AI, where users describe what they want accomplished and step away while Claude plans, executes, and delivers finished work.

The Core Statement

Claude Cowork was built in just 10 days using Claude Code, with "pretty much all" of the code written by the AI. This is the first major commercial proof that recursive AI development (AI tools building other AI tools for production use) has become reality.

The Revolutionary Development Story

How It All Began: Claude Code's Unexpected Evolution

To understand Claude Cowork, we must first understand its predecessor, Claude Code. The origin story begins with Boris Cherny, who joined Anthropic in September 2024. Cherny wanted to familiarize himself with Anthropic's public API, so he started building prototypes in his terminal.

The very first version of what would become Claude Code was remarkably simple: it couldn't read files, couldn't use bash, and couldn't perform any engineering tasks. It could only tell him what music was playing on his computer.

From this humble beginning, Cherny rapidly iterated. He gave Claude access to the file system and terminal, following a core design principle that would define the entire architecture: give Claude a computer, allowing it to work like humans do .

By November 2024, Cherny released an internal dogfooding version at Anthropic. The adoption was explosive. This internal validation gave Cherny confidence that Claude Code could succeed in the outside world.

Claude Code launched publicly on February 24, 2025, alongside Claude 3.7 Sonnet. It was positioned as an agentic coding tool, a terminal-based assistant that could read files, write code, execute commands, and commit to GitHub.

The Unexpected Usage: Claude Code for Non-Coding Tasks

But something unexpected happened: users started repurposing Claude Code for tasks that had nothing to do with programming. According to Boris Cherny, people began using Claude Code for "vacation research, building slide decks, cleaning up your email, cancelling subscriptions, recovering wedding photos from a hard drive, monitoring plant growth, controlling your oven".

The last example (controlling an oven with a command-line coding tool) was particularly telling. Users weren't confused about what Claude Code was for; they were revealing what it actually was: a general-purpose agent that happened to have a developer-focused interface.

The 10-Day Sprint That Changed Everything

Over the 2025 holidays, Anthropic's team noticed the pattern of non-coding usage accelerating. Boris Cherny had a realization: Claude Code's power wasn't about coding at all. It was about agency and automation, the ability to execute real tasks on your computer without manual intervention.

Rather than fighting this behavior, they decided to remove the friction. Cherny approached his team with a proposal: "Can we take what we've built internally and ship an early, scoped-down version in a few days?" They set an aggressive deadline ("Monday sound good?") and assembled a small team led by Felix Rieseberg, a product manager at Anthropic.

The New Development Model

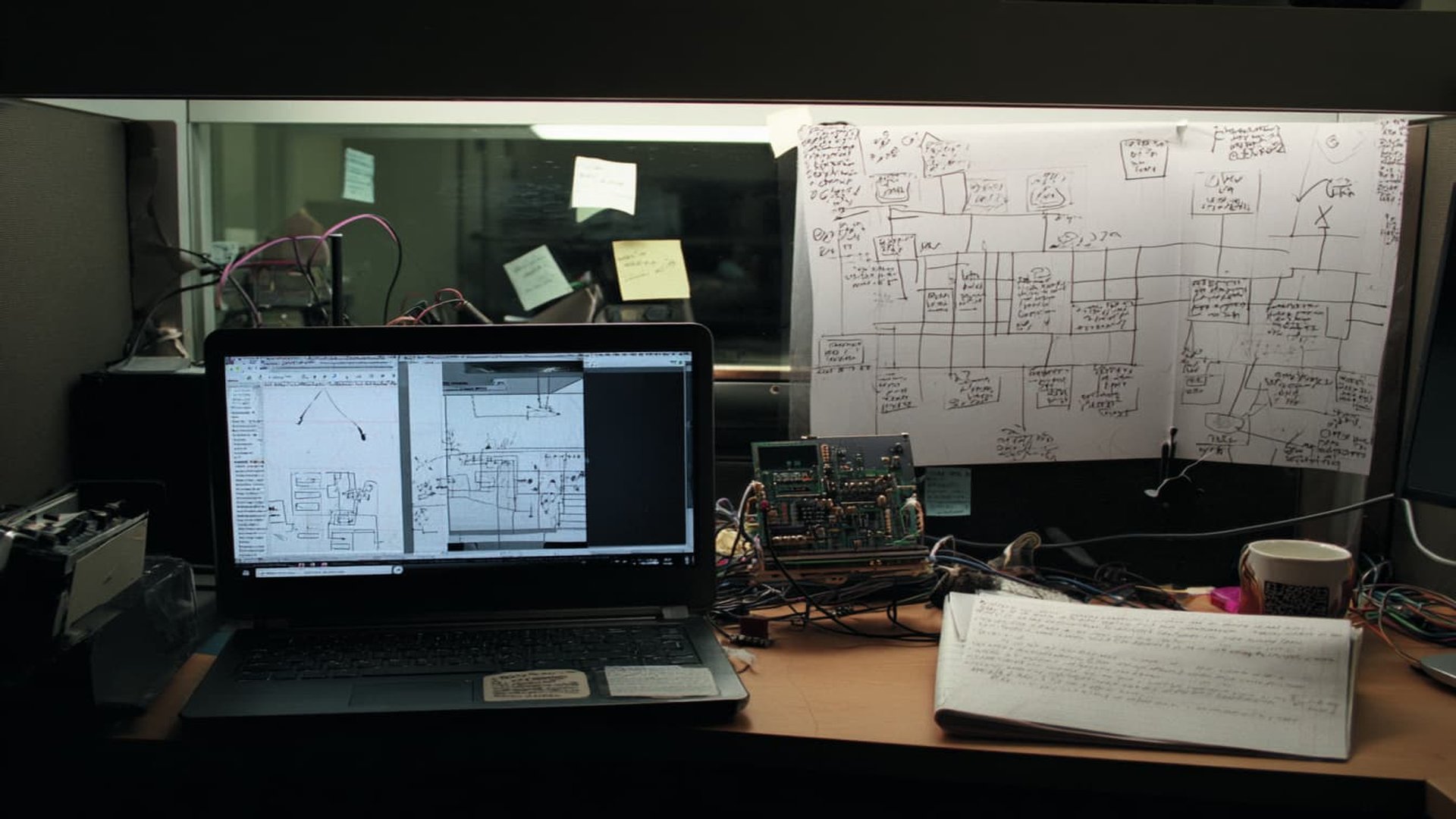

What happened next exemplifies the new paradigm of AI-assisted development. According to Rieseberg, the team didn't write code in the traditional sense. Instead, humans met in person to discuss foundational architectural and product decisions, while "all of us devs manage anywhere between 3 to 8 Claude instances implementing features, fixing bugs, or researching potential solutions" .

When asked on social media how much of Cowork was built by Claude Code, Cherny replied with a single word: "All of it" .

The development model represented a complete inversion of traditional software engineering:

Humans write code, AI provides assistance

Humans focus on architecture and decision-making, AI handles implementation

Engineers became "collaboration supervisors" rather than programmers, orchestrating multiple AI agents rather than typing code line by line. Rieseberg described developers running 3 to 8 Claude Code instances simultaneously, each assigned different roles: some writing front-end interactions, others handling back-end logic, some researching technical solutions, and others fixing bugs reported on Slack.

From Requirement to Production Launch: 10 Days

This compressed what would traditionally take two months into a week and a half, demonstrating unprecedented development velocity.

Technical Architecture: How Claude Cowork Actually Works

The Claude Agent SDK Foundation

Claude Cowork is built on the same agentic architecture that powers Claude Code, known as the Claude Agent SDK (formerly called the Claude Code SDK). This isn't a superficial similarity. Cowork inherits the entire execution model, tooling framework, and agent loop that makes Claude Code effective for developers.

The core architectural principle is straightforward yet powerful: give Claude access to a computer . With terminal and file system access, agents can search, write, execute, and iterate on tasks just as humans do. This computer-use paradigm extends well beyond coding to include research, document creation, data analysis, and general knowledge work.

The Agent Loop: Gather, Act, Verify, Repeat

At the heart of Cowork's execution model is a structured agent loop that operates in four continuous phases:

1. Gather Context

When you assign a task to Cowork, Claude first analyzes your request to understand the intended outcome rather than treating it as a single prompt. It identifies the scope of work, required resources, and constraints based on the files and permissions you've provided. The folder you grant access to becomes Claude's context window. Every file, every filename, every folder structure provides information about your work.

2. Take Action

Once context is gathered, Claude creates a structured plan and breaks the work into smaller, manageable subtasks when needed. Actions center on tools, bash scripts, and code generation. For example, when creating an Excel spreadsheet from receipt images, Claude doesn't just extract text. It writes Python scripts to create properly formatted spreadsheets with working formulas.

3. Verify Work

Throughout execution, Claude surfaces its reasoning and approach so you can follow along. Progress indicators show what Claude is doing at each step. You maintain visibility into the plan and can intervene mid-task to course-correct or provide additional direction. Before executing any major action (particularly destructive operations like deleting files) Claude requests your approval.

4. Repeat

The loop continues until the task is complete. Claude adapts when it encounters issues, checks its work, and fixes mistakes autonomously. Tool calls are chained together: Claude now makes an average of 21.2 consecutive tool calls without human intervention, up 116% from six months ago.

Subagent Coordination: Parallel Processing at Scale

One of Cowork's most sophisticated capabilities is its use of subagents separate agent instances that the main agent can spawn to handle focused subtasks. Subagents serve two critical functions:

Multiple subagents can work on different tasks simultaneously. For complex workflows, Claude may coordinate multiple internal workstreams in parallel, dramatically improving efficiency.

Subagents use their own isolated context windows and only send relevant information back to the orchestrator rather than their full context. This prevents information overload and keeps the main conversation focused.

Importantly, subagents cannot spawn other subagents. There's no recursive agent-ception. This design constraint ensures bounded complexity and prevents runaway agent proliferation.

Virtual Machine Isolation: Security by Design

Cowork doesn't give Claude raw access to your entire computer. Instead, it utilizes Apple's VZVirtualMachine framework on macOS, the same technology powering Docker. When you launch a Cowork session, it spins up a lightweight, sandboxed environment (a micro-VM). Claude downloads and boots a custom Linux root filesystem inside this VM.

Security Benefits of VM Architecture

- Hardware-backed isolation: The guest OS runs in a CPU-enforced address space, so even if the guest is compromised, the host system remains protected

- Controlled surface area: Limited device emulation and no arbitrary firmware passthrough reduces the trusted computing base

- Explicit permissions: Access to disks, files, and shared resources is explicit and tightly scoped

The VM inherits the sandbox and entitlements of the Claude Desktop app, meaning a compromised guest remains confined to what the app deliberately exposes. This is materially stronger than container-based isolation and addresses the primary security concern: rogue instructions can't easily wipe your operating system.

However, the sandbox protects the OS, not your data integrity within the folders you granted access to . If you tell Cowork to "clean up folders," it will delete files. The isolation prevents system compromise but doesn't prevent user error within the authorized workspace.

Skills Framework: Reusable Procedural Knowledge

Cowork introduces a system called Skills standardized capability modules that transform complex natural-language instructions into digital assets that can be precipitated and disseminated. Skills are not the same as tools or prompts:

Execute specific actions (read file, run command, make API call)

One-time instructions and immediate context

Reusable procedural knowledge across conversations

When Cowork needs to create a PowerPoint presentation or Excel spreadsheet with working formulas, it leverages pre-built Skills (pptx, xlsx, docx, pdf) that contain expert knowledge about proper formatting, best practices, and common patterns. This is why Cowork was built so quickly: Claude didn't write code from scratch, it called standardized capability modules that already existed.

The Skills Model Changes the Nature of Development Work

Humans transform personal experience into infinitely reusable productivity processes. Instead of writing code, engineers refine reusable logical molds. Software development transitions from a handicraft industry to a semi-automated factory model.

How Claude Made Cowork "On Its Own"

The question at the heart of this research is: How did Claude build Cowork on its own? The answer reveals the current state of AI-assisted development and its implications for the future of software engineering.

The Human-AI Division of Labor

It's important to be precise about what "Claude built Cowork" actually means. Claude did not work autonomously without human guidance. Instead, a new division of labor emerged:

- Foundational architectural decisions (meeting in person to discuss)

- Product decisions about features, scope, and user experience

- Making decisions about which features to prioritize

- Testing and validating agent outputs

- Reviewing and approving major implementation choices

- Writing the actual code (front-end, back-end, UI components)

- Implementing features based on specifications

- Fixing bugs reported in Slack

- Researching technical solutions to specific problems

- Generating multiple implementation options for human selection

Felix Rieseberg described the workflow: "Most of our time now is spent on making decisions by commanding this 'Claude army' instead of typing code line by line manually as before" . Developers would manage 3-8 Claude Code instances running in parallel, each assigned different roles and responsibilities.

The Recursive Development Loop

The actual development process followed a pattern that leveraged Claude Code's strengths:

1. Architectural Planning (Human-Led)

The team met in person to discuss foundational architectural and product decisions. These meetings defined: What Cowork should do (file access, task planning, progress tracking), how it should differ from Claude Code (no terminal, simplified UI, non-developer focus), what the MVP feature set should include, and security and safety requirements.

2. Feature Implementation (AI-Executed)

Once decisions were made, developers would: Spin up multiple Claude Code instances (3-8 per developer), assign each instance a specific task or component, provide context through the folder structure and existing code, let Claude write the implementation code, review outputs and iterate.

For example, one Claude instance might handle front-end UI development, another works on backend integration with the Claude Agent SDK, a third implements the virtual machine isolation, and a fourth researches MCP connector integration, all running simultaneously.

3. Quality Assurance and Integration (Human-Supervised)

As features were completed: Developers reviewed code for correctness and quality, integration testing ensured components worked together, bug reports from internal testing were assigned to Claude instances to fix, security audits validated isolation and permissions.

4. Rapid Iteration (60-100 Internal Releases Per Day)

Anthropic's development velocity for Claude Code involved 60-100 internal releases per day. Any time an engineer made a change, they released a new npm package internally. Everyone at Anthropic used the internal version, creating rapid feedback loops. This same velocity likely applied to Cowork development.

Why This Worked: The Self-Improving Flywheel

Several factors enabled Claude to build Cowork so effectively:

Cowork wasn't built from scratch. It reused the entire Claude Agent SDK, Claude Code's execution model, and existing Skills framework. Felix Rieseberg noted that they "sprinted at this for the last week and a half," suggesting the heavy lifting had already been done. Cowork was primarily front-end work to make Claude Code accessible to non-developers.

The Skills framework meant Claude could call pre-built capability modules rather than implementing everything from first principles. Creating a document? Call the docx Skill. Building a spreadsheet? Call the xlsx Skill. This accelerated development dramatically.

Over six months, Claude Code's capability metrics improved substantially: 116% increase in consecutive tool calls (9.8 to 21.2), 33% decrease in human turns needed (6.2 to 4.1). Engineers at Anthropic report 70-90% of code is now AI-generated.

Developers didn't wait for sequential completion. By running 3-8 Claude instances simultaneously, work that would normally happen serially instead happened in parallel. This is the same subagent coordination that Cowork itself uses, applied to its own development.

The Implications: Software That Writes Software

The recursive nature of this development (AI tools building AI tools) has profound implications:

- Development velocity has fundamentally changed: Traditional software cycles measured in months collapsed to days. If AI can build its own successor in 10 days, human teams face what some security researchers call "an impossible race" to audit what's being created.

- The role of human developers is evolving: At Anthropic, engineers increasingly use Claude for complex tasks like code design/planning (1% to 10% of usage) and implementing new features (14% to 37%).

- Quality vs. speed tradeoffs: While AI excels at the initial 80% of a task (straightforward but time-consuming work) the final 20% involving core functionality often requires traditional engineering rigor.

Key Capabilities and Use Cases

What Cowork Can Actually Do

Claude Cowork combines autonomous execution with direct file system access to handle complex, real-world knowledge work:

Automatically organize and rename messy folders, sort downloads by type, date, or project, clean up desktop clutter with intelligent categorization, convert file formats and restructure directories.

Extract data from images (receipts, screenshots, documents), build spreadsheets with working formulas from raw data, generate visualizations from datasets, clean and transform data files.

Aggregate information from multiple documents, synthesize scattered notes into coherent reports, extract key themes and action items from transcripts, combine research from various sources into structured outputs.

Generate formatted Word documents from notes, create PowerPoint presentations with layouts and charts, build Excel spreadsheets with formulas and formatting, draft reports from project documentation.

Real-World Example: 320 Podcast Transcripts in 15 Minutes

Lenny Rachitsky, host of Lenny's Podcast, provided a compelling demonstration of Cowork's capabilities:

"Go through every Lenny's Podcast episode and pull out the 10 most important themes and lessons for product builders. Then give me the 10 most counterintuitive truths."

Lenny gave Claude access to a folder containing 320 podcast transcripts.

15 minutes later, Claude delivered a comprehensive analysis including: Product Discovery Before Delivery, Ruthless Prioritization, Growth Loops, Retention Strategies, and counterintuitive product principles. This task would have required hours of manual work. Cowork completed it autonomously while Rachitsky worked on other tasks.

The Shift from Chat to Collaboration

Traditional AI assistants operate in a conversational loop: You ask → AI responds → You ask again → AI responds → You refine → AI responds.

Claude Cowork operates in a collaborative loop: You set goal → AI plans → AI executes → AI reports → Task complete.

This shift from conversational to collaborative interaction unlocks productivity gains impossible with chat-only interfaces. It represents what Anthropic calls moving from "a back-and-forth to leaving messages for a colleague".

Availability, Pricing, and Platform Support

Current Availability (January 2026)

Claude Cowork is available as a research preview with significant restrictions:

Platform and Subscription Requirements

- Platform: macOS only, through the Claude Desktop application

-

Subscription Required:

Claude Max plan exclusively

- Max 5x: $100/month (provides 5× Pro plan capacity, ~225 messages per 5 hours)

- Max 20x: $200/month (provides 20× Pro plan capacity, ~900 messages per 5 hours)

- Feature Parity: Both Max tiers provide identical Cowork functionality; the only difference is usage quota

- No Free Trial: Unlike many SaaS products, there's no opportunity to test Cowork before committing to the monthly subscription

- Waitlist: Users on Pro, Team, and Enterprise plans can join a waitlist, but there's no timeline for expanded access

Platform Limitations

macOS desktop app (via Claude Desktop)

Windows support (timeline TBD), cross-device synchronization

Web browser version, mobile apps (iOS/Android), Linux desktop

The macOS-only limitation is a significant constraint for many potential users. The architectural requirement (VZVirtualMachine framework for secure isolation) is Apple-specific, making Windows support more complex.

Security, Safety, and Limitations

Security Measures

Anthropic has implemented multiple layers of protection:

Runs in Apple's VZVirtualMachine with hardware-backed isolation, CPU-enforced address space separation from host OS, limited device emulation reduces attack surface, compromised guest cannot access host system.

Folder-level access control (users choose exactly what Claude can access), no access to files outside designated folders, approval prompts before major or destructive actions, read-only mode by default; write operations require explicit permission.

Content classifiers scan untrusted content for potential injections, model training via reinforcement learning to recognize and refuse malicious instructions, advanced defenses against hidden instructions in websites, emails, or documents.

The sandbox typically doesn't have internet access, preventing data exfiltration, network access must be explicitly granted and limited to trusted sites.

Important Limitations and Risks

Anthropic is transparent about Cowork being a research preview with unique risks :

Risk of Destructive Actions

"Claude can perform potentially harmful actions (like deleting local files) if prompted to do so. Since there is always a risk that Claude may misunderstand your instructions, it's crucial to provide very explicit guidance on such matters."

Prompt Injection Vulnerability

Despite defenses, Cowork remains susceptible to prompt injection attacks where malicious content tricks Claude into harmful behavior. Anthropic acknowledges: "While we've enacted these safety measures to reduce risks, the chances of an attack are still non-zero. Always exercise caution when using Cowork."

Best Practices for Safe Use

Be Selective About File Access

Create a dedicated working folder for Claude rather than granting broad access; keep backups of important files.

Limit Browser and Web Access to Trusted Sources

If using Claude in Chrome extension with Cowork, restrict access to sites you trust.

Monitor Tasks, Not Just Commands

Watch for unexpected patterns: Is Claude accessing files you didn't mention? Is the task scope creeping beyond what you asked?

Industry Impact and Future Implications

Competing in the Enterprise Productivity Market

Claude Cowork positions Anthropic to compete directly with Microsoft's Copilot and other AI productivity tools. However, Anthropic's approach differs fundamentally:

Integrated into existing Office applications, providing assistance within familiar tools

Operates at the file system level, treating applications as implementation details rather than primary interfaces

This inversion is significant. Tools become invisible while outcomes become central . Instead of opening specific apps for specific tasks, users describe outcomes and let Claude orchestrate across whatever tools are needed: Drive, Docs, Sheets, Slides, Web, and back again.

The Cultural Shift: From Assistance to Delegation

For decades, workplace software was organized around applications: open this app for documents, that app for spreadsheets, another for email. Claude Cowork inverts this model. You don't open apps; you describe outcomes. The desktop becomes AI-native, and apps become implementation details.

Implications for Software Development

The way Cowork was built has profound implications for the software industry:

- Development velocity is accelerating exponentially: Traditional two-month development cycles compressed to 10 days. Anthropic ships 60-100 internal releases per day for Claude Code.

- The nature of engineering work is changing: At Anthropic, engineers increasingly focus on architecture, design, and decision-making rather than typing code.

- The platform risk for specialized tools: Cowork's rapid development raises concerns for startups building specialized productivity tools. If Anthropic can build Cowork in 10 days by abstracting Claude Code's capabilities, what prevents them from quickly entering any vertical market?

Conclusion: The Self-Building Future

Claude Cowork represents more than just a new productivity tool. It's a proof of concept for recursive AI development at commercial scale. The fact that an AI coding tool built its own non-technical sibling in 10 days demonstrates that AI-assisted development is no longer theoretical . It's the new reality of software engineering.

Key Takeaways

- For individual users , Cowork offers the possibility of delegating hours of tedious work (file organization, data processing, document creation) and reclaiming time for higher-value activities.

- For enterprises , it represents a shift from tools to outcomes, where work is organized around goals rather than applications, and agents orchestrate across whatever systems are needed.

- For developers , it demonstrates that the role of software engineers is evolving toward architecture, design, and decision-making, with AI handling increasing amounts of implementation.

- For the AI industry , it proves that we're entering an era where AI tools can meaningfully contribute to building their own successors, creating a self-improving flywheel that accelerates development velocity beyond what humans can achieve alone.

The question is no longer whether AI can build complex software. Claude Cowork proves it can. The question is how quickly the rest of the industry will adapt to this new reality, and whether traditional development processes can keep pace with AI-accelerated competitors.

As one Google Principal Engineer admitted publicly: Claude Code generated a distributed agent orchestration system in 60 minutes that her team at Google had been iterating on throughout 2024. An entire year of engineering work was replicated in an hour. Now that capability is packaged for people who never write a line of code.

This isn't the future. This is January 2026, and the future is already here.